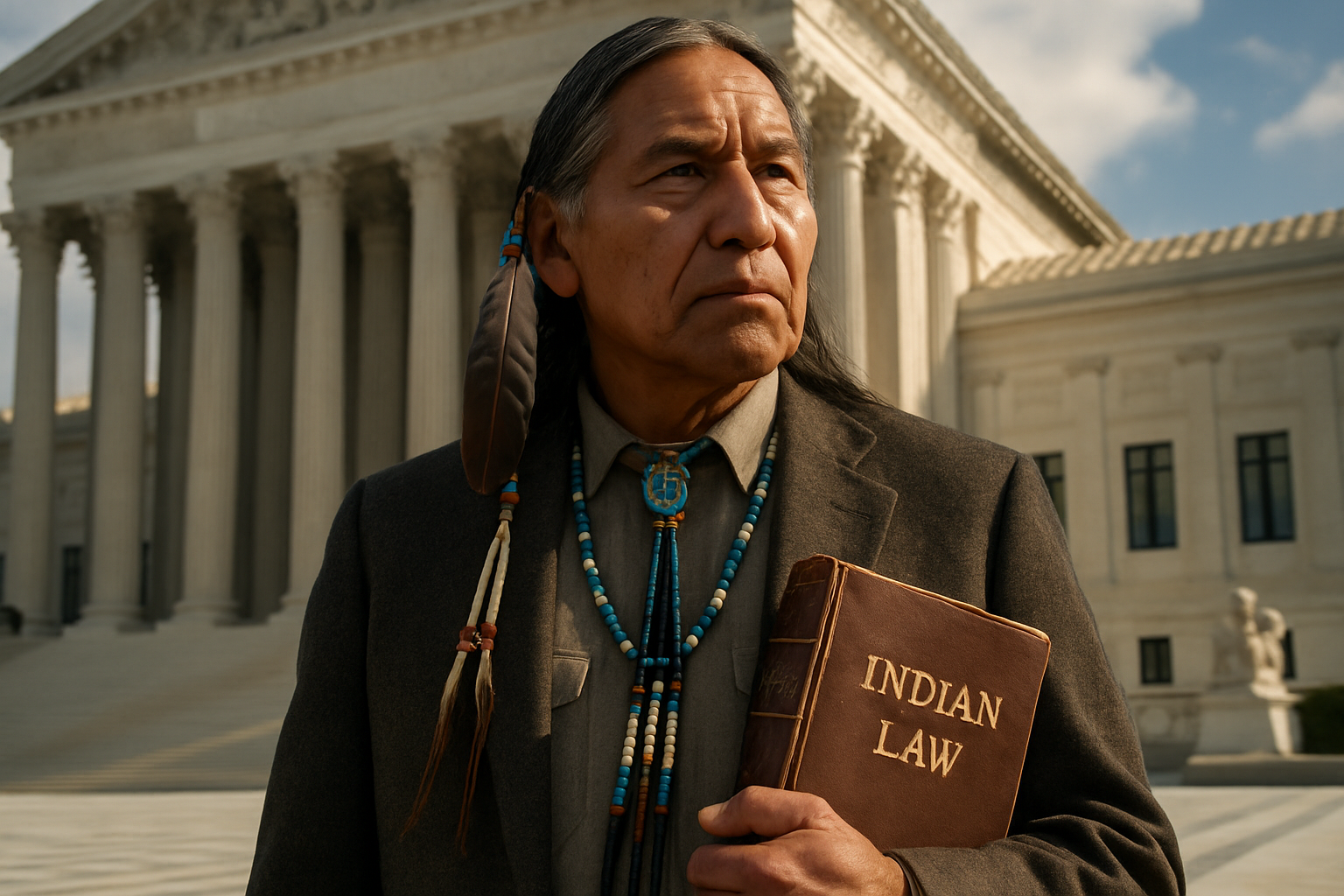

Tribal Sovereignty in Modern Environmental Governance

The intersection of tribal sovereignty and environmental law presents a dynamic frontier in American jurisprudence that continues to evolve. Native American tribal governments increasingly assert their rights to manage natural resources and environmental protection within their territories, creating a complex legal landscape that balances tribal authority with federal and state regulations. This legal relationship remains consistently in flux as court decisions, administrative policies, and legislative actions redefine the boundaries of tribal environmental authority. Understanding these developments provides crucial insight into one of the most significant aspects of federal Indian law and environmental governance in the United States today.

The Legal Foundations of Tribal Environmental Authority

Tribal sovereignty serves as the cornerstone for Native American environmental governance, originating from tribes’ status as pre-constitutional sovereign entities. The Marshall Trilogy—three Supreme Court cases decided between 1823 and 1832—established tribes as “domestic dependent nations” with inherent powers of self-government. This foundational doctrine has evolved through subsequent judicial decisions, treaties, and legislation. The Environmental Protection Agency’s 1984 Indian Policy formally recognized tribal governments as the appropriate authorities for making environmental decisions affecting their lands. This recognition was further solidified through amendments to major federal environmental statutes including the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, and Safe Drinking Water Act during the 1980s and 1990s, which included provisions for “Treatment as a State” (TAS) status allowing qualified tribes to administer environmental programs within their jurisdictions. These legal mechanisms have created pathways for tribes to exercise environmental authority beyond what was previously possible, though implementation remains inconsistent.

Jurisdictional Complexities in Environmental Protection

The jurisdictional framework governing tribal environmental authority represents a complicated patchwork of legal doctrines. Tribes generally exercise regulatory authority over their members and trust lands, but questions arise regarding authority over non-member activities and fee lands within reservation boundaries. The 1981 Montana v. United States decision established a presumption against tribal civil regulatory authority over non-members on non-Indian land within reservations, though it created exceptions when activities threaten tribal health and welfare—a principle frequently invoked in environmental contexts. Subsequent cases have further refined these jurisdictional boundaries, creating significant legal uncertainty. Additionally, Public Law 280 and similar statutes have transferred certain regulatory authorities to states in some regions, creating additional complexity. This jurisdictional maze means tribal environmental initiatives often operate within contested legal terrain, requiring sophisticated legal strategies and intergovernmental coordination to achieve effective environmental protection across reservation landscapes.

Water Rights and Management Innovations

Water rights represent perhaps the most significant environmental legal issue for many tribal nations, particularly in the arid western United States. The 1908 Winters doctrine established that when reservations were created, water rights were implicitly reserved to fulfill reservation purposes. These rights typically carry priority dates coinciding with reservation establishment, making them senior to many non-tribal water users. However, quantification of these rights has historically required lengthy and expensive litigation or negotiated settlements. Recent developments have seen tribes leveraging these water rights in innovative ways, including instream flow protections for cultural and ecological purposes, water marketing arrangements, and watershed co-management agreements with other governments. The 2018 settlement between the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and Montana exemplifies this trend, quantifying tribal water rights while establishing cooperative management mechanisms. These developments demonstrate how tribes are transforming theoretical water rights into practical governance tools that advance both environmental protection and tribal economic development.

Climate Change Response and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Climate change presents existential threats to many tribal communities while simultaneously creating new openings for tribal environmental leadership. Tribes are increasingly recognized as possessing invaluable traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that offers historical perspectives on ecological change and adaptation strategies. Federal agencies have begun formally incorporating TEK into climate planning processes, as evidenced by the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Tribal Climate Resilience Program and similar initiatives across federal departments. Tribes themselves are developing sophisticated climate adaptation plans that integrate scientific data with indigenous knowledge systems. The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community’s climate adaptation plan represents a pioneering example, addressing sea level rise through both infrastructure adaptations and cultural resource protections. These initiatives demonstrate how tribes are positioning themselves as leaders rather than victims in climate governance, though significant funding and capacity challenges remain for many tribal governments seeking to implement comprehensive climate strategies.

Emerging Models of Tribal-Federal Environmental Co-Management

Recent years have witnessed the emergence of innovative co-management arrangements between tribal nations and federal agencies. These frameworks move beyond consultation toward genuine power-sharing in environmental decision-making. The Bears Ears National Monument, initially designated in 2016, created an unprecedented management commission including representatives from five tribal nations alongside federal agencies. Although subsequently modified, this model illustrated possibilities for meaningful tribal participation in public lands management. Similarly, the 2020 restoration of the National Bison Range to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes represents a landmark transfer of wildlife management authority. These developments suggest a potential paradigm shift in federal-tribal environmental relations, moving from an era of consultation toward one of genuine collaborative governance. However, these arrangements remain vulnerable to political shifts and implementation challenges. The future trajectory of these co-management innovations will significantly impact both tribal sovereignty and environmental protection across large landscapes that transcend jurisdictional boundaries.