Nutritional Chronotherapeutics: Timing Your Diet With Your Body Clock

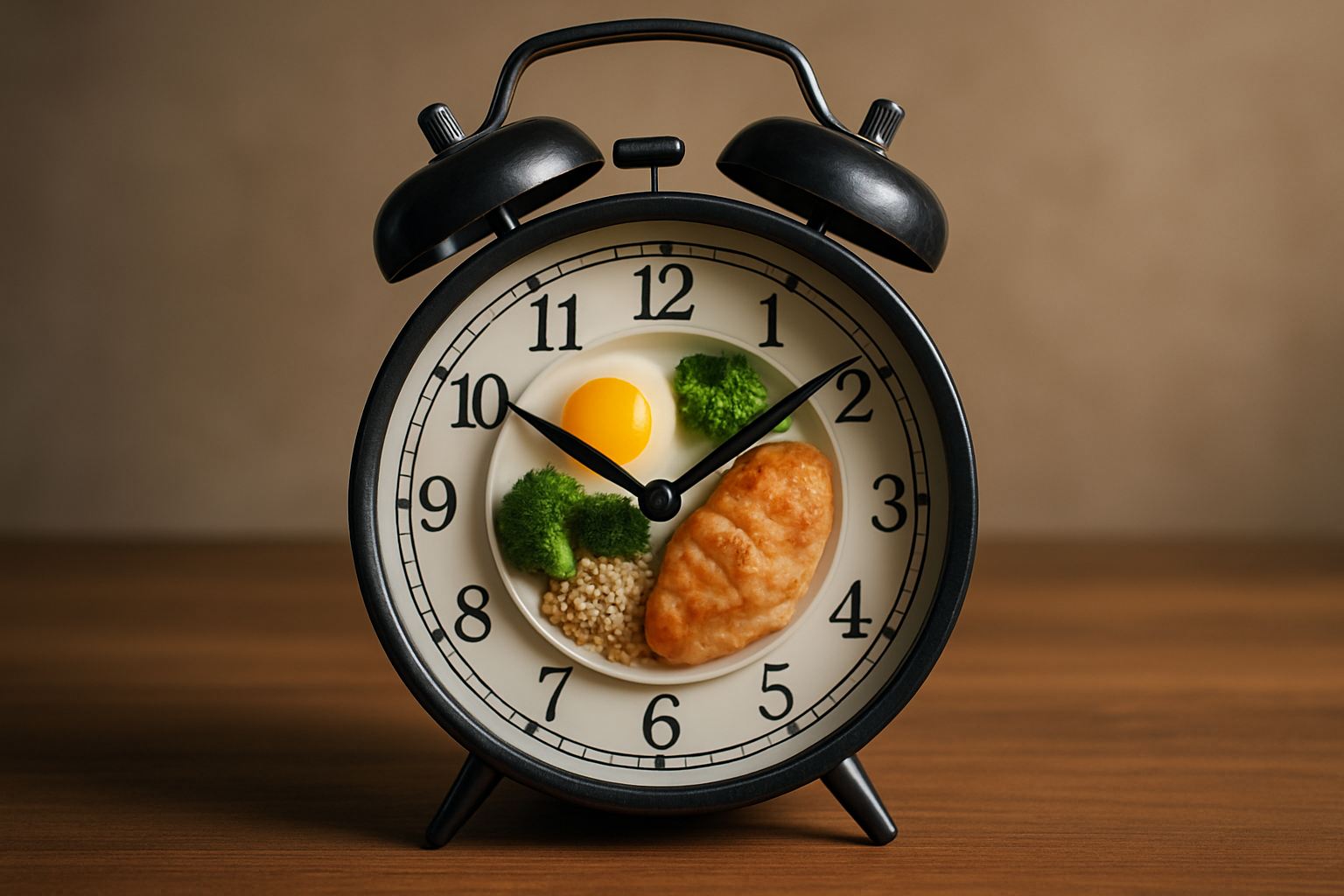

The interplay between when we eat and our biological rhythms represents one of nutrition science's most fascinating frontiers. Nutritional chronotherapeutics—timing specific foods and nutrients to align with your body's circadian rhythms—offers a revolutionary approach to health optimization beyond traditional dietary advice. This emerging field suggests that when you eat may be just as critical as what you eat, potentially influencing everything from metabolic health to cognitive performance and immune function. Could the timing of your meals be the missing link in your wellness journey?

Understanding Your Body’s Internal Clock

Our bodies operate on a complex network of biological timekeepers collectively known as the circadian system. This intricate chronological organization extends far beyond simply regulating sleep and wakefulness. Nearly every tissue and organ in the human body contains molecular clocks that influence countless physiological processes throughout the day. These include hormone secretion, enzyme activity, nutrient absorption, and cellular repair mechanisms.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus, serves as the master regulator of this system, synchronizing peripheral clocks throughout the body. While light exposure represents the primary environmental cue for the SCN, research increasingly demonstrates that food timing provides powerful signals to peripheral clocks, particularly in metabolic tissues like the liver, pancreas, and adipose tissue.

Studies reveal that disruption of circadian rhythms through irregular eating patterns correlates with increased risk of metabolic disorders, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. This understanding forms the foundation of nutritional chronotherapeutics—strategically timing nutritional intake to complement rather than conflict with our internal timekeeping mechanisms.

The Metabolic Timing Advantage

Our metabolic machinery functions differently throughout the 24-hour cycle, creating distinct windows of opportunity for nutrient processing. Morning hours typically feature enhanced insulin sensitivity, more efficient glucose metabolism, and heightened thermogenesis—the body’s ability to burn calories as heat. This makes morning an optimal window for carbohydrate consumption.

Research from Vanderbilt University shows that identical meals consumed at different times produce dramatically different metabolic responses. A moderate-carbohydrate meal consumed at breakfast triggers lower blood glucose spikes compared to the same meal eaten at dinner. This “metabolic morning advantage” appears linked to insulin sensitivity patterns that peak early in the day and gradually decline as evening approaches.

Evening metabolism shifts toward fat storage rather than utilization, with reduced thermogenesis and decreased glucose tolerance. This physiological shift explains findings from prospective cohort studies showing that individuals who consume larger proportions of their daily calories later in the day face higher rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome compared to those with early-weighted eating patterns—even when controlling for total caloric intake and nutritional composition.

Practical application involves front-loading calories and carbohydrates earlier while emphasizing protein and fibrous vegetables during evening meals. This approach aligns nutritional intake with the body’s natural metabolic rhythms rather than working against them.

Chronotype-Based Nutrition Strategies

Chronotype—your biological preference for morning or evening activity—significantly influences the optimal timing of nutritional intake. Researchers identify four primary chronotypes: morning types (lions), day types (bears), evening types (wolves), and insomnia-prone types (dolphins). These distinctions extend beyond mere preferences, reflecting genetic variations in clock genes and hormonal patterns.

Each chronotype presents unique metabolic characteristics requiring personalized nutritional timing strategies. Morning chronotypes typically exhibit earlier insulin sensitivity peaks and may benefit most from conventional nutritional timing advice. Evening chronotypes, however, show delayed metabolic profiles, with insulin sensitivity peaking later in the day.

Dr. Courtney Peterson’s research at the University of Alabama suggests that extreme evening types may benefit from delaying breakfast and shifting their eating window later to align with their biological rhythms. This personalized approach acknowledges that standardized recommendations for meal timing may not serve all chronotypes equally well.

The emerging field of chronotype-specific nutrition represents a significant advancement toward truly individualized dietary recommendations. Self-assessment tools like the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire help individuals identify their chronotype, allowing for targeted adjustments to meal timing that complement rather than contradict innate biological rhythms.

Strategic Fasting Windows

Time-restricted eating (TRE) has emerged as a practical application of nutritional chronotherapeutics accessible to most individuals. This approach involves confining all caloric consumption to a specific daily window, typically 6-10 hours, thereby extending the natural overnight fasting period.

The scientific rationale centers around metabolic flexibility—the body’s capacity to switch between glucose and fat metabolism efficiently. Extended daily fasting periods activate cellular cleaning mechanisms like autophagy while allowing metabolic organs to complete full cycles of activity and recovery. Research from the Salk Institute demonstrates that confining the same caloric intake to a shorter daily window improves multiple health markers in experimental models.

Human studies show promising metabolic benefits even without caloric restriction. A landmark study published in Cell Metabolism found that overweight adults who restricted eating to an 8-hour window (10am-6pm) showed improved insulin sensitivity, reduced blood pressure, and enhanced antioxidant activity compared to those eating across 12+ hours—despite comparable caloric intake.

The timing of the eating window appears crucial. Research from Pennington Biomedical Research Center suggests that earlier windows (8am-4pm) may offer greater metabolic benefits than later windows (12pm-8pm) for most chronotypes. This aligns with natural patterns of insulin sensitivity and the thermogenic advantage of daytime eating.

Dr. Satchin Panda, a pioneer in circadian nutrition research, suggests starting with a 12-hour eating window and gradually narrowing it based on individual response and lifestyle compatibility. This approach makes chronotherapeutic benefits accessible without overwhelming adherence challenges.

Nutrient-Specific Timing Considerations

Beyond general meal timing, emerging research suggests that specific nutrients may have optimal consumption windows based on circadian variations in metabolic pathways. These time-based nutrient strategies offer another dimension of nutritional chronotherapeutics worth exploring.

Protein timing deserves particular attention. Exercise physiologists have long recognized that post-exercise protein consumption enhances muscle protein synthesis. Recent chronobiology research adds nuance, suggesting that moderate protein distribution throughout the day may optimize muscle maintenance while supporting satiety. Evening protein intake appears particularly valuable for overnight muscle recovery and morning metabolic rate, challenging the conventional wisdom to minimize evening eating.

Essential micronutrients also demonstrate time-sensitive effects. Fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin D show enhanced absorption when consumed with morning meals, aligning with natural digestive enzyme peak activity. Conversely, minerals like magnesium and zinc demonstrate optimal effectiveness when taken in the evening, potentially supporting sleep quality and overnight recovery processes.

Even the timing of antioxidant consumption warrants consideration. Research indicates that antioxidant supplementation immediately before or after intense exercise may blunt adaptive responses, while strategic timing several hours away from training maximizes both exercise adaptation and antioxidant benefits.

These emerging insights highlight the complexity of nutritional chronotherapeutics—a field that considers not just what we eat, but precisely when specific nutrients are most beneficial within our biological rhythm context.

Practical Chronodietary Guidelines For Everyday Life

-

Begin your day with a nutrient-dense breakfast containing protein and complex carbohydrates within 1-2 hours of waking to synchronize peripheral clocks.

-

Consider your chronotype when establishing meal timing—earlier chronotypes benefit from earlier eating windows, while evening types may function better with delayed breakfast.

-

Front-load carbohydrates earlier in the day when insulin sensitivity peaks for most people.

-

Aim for at least 12 hours of overnight fasting to support cellular cleanup mechanisms.

-

Minimize eating during your biological night—the period when melatonin is actively being secreted.

-

Maintain consistent meal timing across weekdays and weekends to prevent “metabolic jet lag.”

-

Consume caffeine primarily during the morning hours, avoiding intake after 2pm to prevent sleep disruption.

-

Schedule protein intake strategically around exercise sessions to maximize muscle protein synthesis.

The field of nutritional chronotherapeutics represents a significant evolution in our understanding of diet and health. By aligning our eating patterns with our internal biological rhythms, we gain access to optimization strategies that traditional nutritional approaches overlook. The science clearly demonstrates that when we eat matters profoundly, offering relatively simple yet powerful adjustments that can enhance metabolic health, cognitive performance, and overall well-being. As research in this area continues to develop, the personalization of meal timing according to individual chronobiology may soon become as fundamental to nutritional recommendations as macronutrient composition and caloric intake.